Not surprisingly, the two regions have historically seen different impacts from El Niño. Can the past give us a hint at what the future may hold?

The black line represents the 2014 August-October ONI value.

Red dots show ONI values greater than 0.5 (El Niño), blue dots show values less than -0.5 (La Niña), and black dots are neutral ONI values. Part (a) is Climate Division 91, San Joaquin Valley, while (b) is Division 93, the southern California coast. Total precipitation for December-March (vertical axis) compared to Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) values in August-October (horizontal axis). The dashed line points out the value of the August-October 2014 ENSO index value (called the Oceanic Niño Index).įigure 2. Part (a) shows conditions across southern California and part (b) shows the San Joaquin Valley, where most of the agriculture in California is grown. (Although personally, I think part (b) looks like a bunny.) Figure 2 shows how, in the past, sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies during the August – October (ASO) time frame were related to the subsequent December-March precipitation totals for certain regions in California. And no, Figure 2 is not a Rorschach test. To show this, instead of giving you probabilities and numbers, I am going to let your eyes tell you the story. The second issue is that, as mentioned previously on the blog, no two El Niño events are the same, and thus their impacts aren’t either. You wouldn’t expect the climate to be the same in northern and southern California, so you shouldn’t expect the impacts of El Niño to be the same either. The first issue is that California is a BIG place. So you may wonder, is it a slam dunk that a developing El Niño causes above-average rain for California? And finally we have discussed exactly what we mean when we use probabilities in these types of forecasts. We have even discussed what the upcoming winter forecast will be for the United States. We have previously touched on the large-scale impacts an El Niño could have on the United States, namely shifting storm tracks around North America, potentially resulting in an abundance of rainfall for parts of California. The issue since drought first arrived back in December 2011 is that Mother Nature missed this memo. Drought Monitor.ĭuring a normal year in California, rainfall picks up in intensity throughout the late fall into winter. Map by NOAA, based on data provided by the U.S. Currently, 99.72% of the state is under drought with 55.08% of California experiencing “D4,” or Exceptional Drought. Drought conditions as of November 18, 2014. The California Department of Water Resources averages data from 19 weather stations spanning the state and generates averages for three regions.Figure 1. Rainfall in California from a monthly perspectiveĭecember and January rainfall totals have been above average in several parts of the state. Napa was nearly 5 inches higher at 15.19 inches, and Sonoma's 15.8 inches beat its previous high of 12.56 inches.

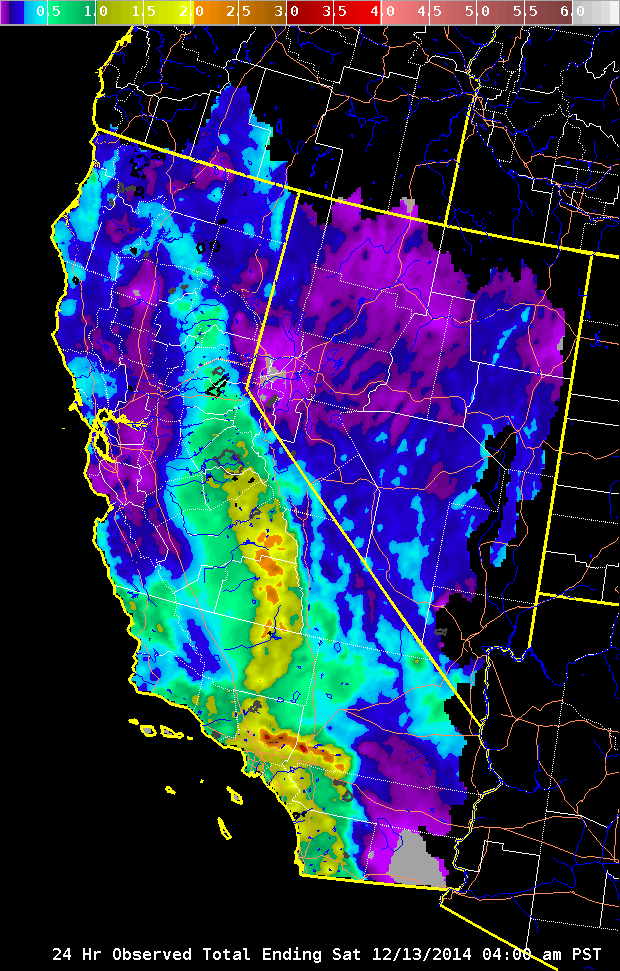

Downtown Oakland received 18.33 inches, topping the previous high by 8 inches. Lorber's calculations put all three locations well above their former records. 16 in areas around Oakland, Napa and Sonoma. Records were toppled for the 22-day period from Dec. That doesn't mean records weren't broken around the state, Lorber said. San Francisco's total rainfall of 17.64 inches was second to that rainy season more than 160 years ago, when the same time period saw 18.49 inches. "Downtown San Francisco is our only site that has records that far back." 16) due to even more exceptional rainfall in the Great Flood from December 1861 to January 1862," National Weather Service meteorologist Jeff Lorber said. "Downtown San Francisco did not see record rainfall in this period (Dec. The data, from Oregon State University’s PRISM product, is based on the network of real-time precipitation sensors spread throughout California.įor some cities.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)